Travelling to Japan to meet the gentle genius behind Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle…

Travelling to Japan to meet the gentle genius behind Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle…

They call him the Walt Disney of Japan. He’s adored by Kurosawa and Spielberg. If you ask Pixar godhead John Lasseter, “He’s the greatest director living today.” So when Hayao Miyazaki invited Total Film to visit him in Japan, take a special tour of Studio Ghibli and find out exactly why this reclusive Japanese fabulist is the greatest animator the movies have ever seen, we couldn’t say no…

A small, leaf-covered building on the edge of Tokyo, Studio Ghibli was founded by Miyazaki and fellow animator Isao Takahata in 1985. Its movies have been topping the Japanese box office for decades. Ghilbi has shown the world a daredevil princess fighting for her people (Nausicaa: Valley Of The Wind) , giant, gentle robots protecting a Laputa’s flying island (Castle In The Sky

), flying cat-buses that only children can see (My Neighbour Totoro

), a teenager witch and her talking moggy (Kiki’s Delivery Service

) and a maverick pig who flies a WWII hydroplane (Porco Rosso

). Eco-warrior epic Princess Mononoke

became Japan’s biggest all-time till-ringer in 1992, before Spirited Away

blew Titanic out of the water to become the highest-grossing film in Japan’s history. Toy Story, Finding Nemo and The Incredibles made Pixar the daddy of modern animation in the West, but US ‘toon meastros – especially Pixar chief John Lasseter – worship Miyazaki like a god.

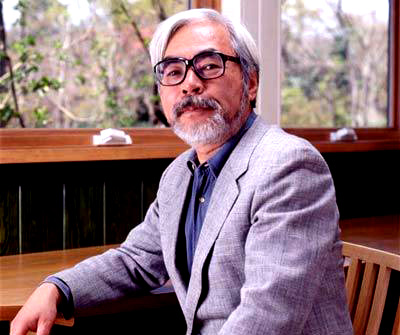

The man who greets Total Film on the steps of Ghibli, though, is gratifyingly un-godlike. Wearing a plain short-sleeved shirt and tan trousers, Miyazaki is a most unassuming deity, his grey hair neatly trimmed and kind eyes hiding behind thick, black-rimmed spectacles. Born in year of Pearl Harbor, the young Miyazaki took refuge from blasted post-war Japan in an imagined Europe, Western literature and the paintings of Chagall and Bosch, fuelling his imagination to astonishing result. Now, at 64 years old, he’s cemented his rep as one of the greatest animator-filmmakers in the history of the medium. Howl’s Moving Castle, based on Diana Wynne Jones’ novel

about a teenager (voiced in the English dub by Emily Mortimer) transformed into a 90-year-old woman, will be his ninth movie for Ghibli. Fair to say, Miyazaki gets the joke.

“It is true I am 64 years old now,” smiles the animator. “But I realise that inside I’m still a little boy. Of course, if you look in the mirror I’m old, but I haven’t changed at all. I guess reading Diana Wynne Jones’ story, I felt some kind of sympathy.” Stepping inside the studio, we come face to face with our first Ghibli hero: it’s a large wooden effigy of a creature that looks something like a giant owl. Crossbred with a cat. This is Totoro, the cuddly forest-spirit star of Miyazaki’s breakout hit My Neighbour Totoro, beloved studio logo and one of the many wondrous characters that populate his films.

Inside the light, airy offices, young animators stoop over wooden desks, sketching and painting backgrounds and character frames in painstaking detail. Paintpots and design etches are stacked everywhere, vastly outnumbering the computer workstations. Unlike Pixar’s CG-powered adventures, Studio Ghibli’s flights of invention come from the ink-jar not the pixel palette. “With the advent of computer graphics, I did feel that a very important chunk of my work was lost,” says Miyazaki. “Even though much more can be done that wasn’t possible before, I’m holding on to my pencil.” It’s a working practise that demands staggering commitment to keep the dream factory churning. Miyazaki has it by the bucketload. In Ghibli’s early days, he would work from 9am to 4:30am. In recent years, he’s eased off a little. The old man goes home at midnight. If comparisons with Walt Disney don’t fit, then perhaps multi-tasking auteur Robert Rodriguez is a better analogy. With his desk sitting innocuously in the corner, Miyazaki not only writes and directs his films, but designs every character and etches each storyboard, personally checking and redrawing the countless film cels. Once declaring that his idea of a vacation is a nap, he created WWII flyboy (well, fly-pig) actioner Porco Rosso single-handedly when Ghibli couldn’t afford more man-power. The rule here, Miyazaki explains, is that CG must account for no more than 10 percent of the images in any of his movies. Case in point is Howl’s Moving Castle’s titular fortress, a scuttling mansion with turrets and balconies and chimneys thrusting out from every surface. On-screen, Miyazaki’s animators demonstrate how the Castle is designed in 3-D, before hand-drawn 2-D textures are layered over the top, giving vibrant life to its four stomping legs.

On the way out of the studio, we pass another portrait of Totoro on the wall. This time, he has some familiar company: Sulley and Mike from Monsters Inc, surrounded by the scrawled signatures of John Lasseter’s Pixar team. Miyazaki first met a young Lasseter on a brief business trip to Disney in 1981 (“Unlike the John Lasseter of today, he was a very slender man!”) and the two have enjoyed a 20-year friendship. Lasseter freely admits that whenever Pixar hit writers’ block, they all pile into their screening room and watch a Ghibli movie. But when it comes to spotlighting the difference between Hollywood’s leading animators and himself, Miyakazi barely pauses. “John Lasseter wants to guide children,” he smiles slowly as he takes out a cigarette, “while I want to get lost with them. That’s the difference. I think that if you are very genuine in doing films for young children, you must aim for their heads, not deciding for them what will be too much for them to handle. What we found was that the children actually understand the movies more than the adults.”

Hollywood certainly didn’t get it. After US distributors mangled the US video release of his debut feature Nausicaa: Valley Of The Wind, Miyazaki slammed the door on international distribution until 1996, when Disney bought the rights to distribute the studio’s works overseas. Even then, Princess Mononoke scored only limited release and flopped in the States. Maybe it was Miyazaki’s refusal to paint easy portraits of good and evil. “I know this is considered mainstream, but I think it’s rotten,” he nods. “This idea that whenever something evil happens someone particular can be blamed and punished for it, in life and in politics, it’s hopeless.” Maybe that was it. Or maybe it was the fact that, when Miramax started the dub of Mononoke, Miyazaki sent a Samurai sword to Harvey Weinstein with a note reading, “No cuts”. Either way, it took John Lasseter to finally bulldoze Disney into releasing Spirited Away with full aplomb, the Pixar man supervising the project personally. Result? Critical praise, major box-office and an Academy Award. Harvey and Hollywood got the point.

Still, ever the anti-tinseltown, Ghibli resists all attempts to whore their creations in a merchandising avalanche. Miyazaki invites fans to enter his world through the Studio Ghibli Museum instead. It’s a museum of the mind, designed to the last detail by the filmmaker (yes, this guy does architecture, too), with elf-sized doors, secret passageways, propeller-like ceiling-fans and spiral staircases. Sketches and storyboards paper the walls, model aeroplanes and flying dinosaurs hang from the ceiling, while the floor is stacked with books: The Best Children’s Books In The World, Great Military Battles, Mysteries Of The Afterlife… Outside, guarding the entire complex, is Castle In The Sky’s towering metal robot. “These things represent what’s inside me,” explains Miyazaki. “I wanted to show the roots of inspiration, that feeling of something bursting in your chest. Personally, I think there’s still too much merchandise out there, but perhaps these rooms will give a child a glimpse into my heart.”

And it’s his films that aim to open a glimpse into our own hearts. Powered by literature, folklore, myth and history, Miyazaki works on the same plane as CS Lewis, JRR Tolkein and Lewis Carroll. His astonishing worlds are populated by cosmic wizards, archaic machines and fantastical creatures. It’s a galaxy away from the super-smart kiddie pop-culture of movies and TV. “The truth is, I’ve watched almost none of it,” he says with a smile. “The only images I watch regularly come from the weather report.” A joke? Maybe not. Far from Japanimation’s violent megalopolises and tentacle-horror, Miyazaki’s landscapes are a character in themselves. In their eye for the magic and myth of everyday life, Ghibli’s movies are time-capsules of childhood experience, movies that pause wide-eyed to listen to the wind and the trees. For all the visual delight, there’s a sadness to capturing those fragile moments before a child becomes an adult. “All children are tragic because they’re born with infinite possibilities and really the process of childhood is about cutting off many of those possibilities,” admits Miyazaki, whose movies cast a sad, mistrustful eye toward the present, particularly in the eco-warnings of Nausicaä and Princess Mononoke and the anti-war rumblings of Howl’s Moving Castle. “When I found that people in Baghdad can watch themselves being bombed, I thought, what a horrible, magical world we’re living in. We shouldn’t stick too close to everyday reality but give room to the reality of the heart, of the mind and of the imagination,” he explains. “When making a film, I use all my childhood memories: these are things that can help us in life.” Exploding the boundaries between life and death, reality and fantasy, imagination and insanity, it’s the kind of storytelling that makes Disney look, well, mickey mouse.

“One thing you can be sure of,” says a character near the end of Howl’s Moving Caslte. “Hearts change.” Transformations – wizards into birds of prey, greedy parents into pigs, boys into dragons or young girls into old women – are at the heart of Miyazaki’s world. They’re a reminder of animation’s real meaning: to set in motion, to bring to life. Moving pictures, indeed.

Publication: Total Film

Hi! I was surfing the net and found your blog post… nice! I love your blog. 🙂 Cheers! Melissa. G.