The full story behind the most influential CG movie ever made…

The full story behind the most influential CG movie ever made…

Wyatt Earp was puzzled. Sitting on a horse in the middle of the hot Arizona desert, he scratched his huge handlebar moustache. He looked again the script that had been handed to him. “I’m reading this thing called Tron,” remembers Bruce Boxleitner, shooting made-for-TV Western I Married Wyatt Earp

at the time. “I’ve got no clue what it’s about. No man, I don’t even know what this is. What is this?”

‘This’ was the most groundbreaking CGI movie ever. The first film ever to use computer-generated effects to create an immersive 3D world, Tron would help blast cinema into a new digital age where a man could fight gladiators in ancient Rome, transform into a liquid metal cyborg or bring a toy cowboy to life. Wyatt Earp was puzzled alright.

Weirdly, the run-up to Tron involved an elephant lifting weights, a crocodile doing the high-jump and a bird on the parallel rings. Back in the late 70s, Steve Lisberger was a 25-year-old animator making TV commercials and animated spots for Sesame Street. His latest gig was The Animalypics, a spoof of the 1986 Olympics.

Lisberger wasn’t excited about animals. He was excited about some test-footage he’d shot using a technique called ‘backlit animation’. “It made things pulse and glow by shining light directly into the camera,” says Lisberger.”One of our animators designed this liquid neon character. He smashed these two discs of light together, which exploded, circled around and came back. Since he was electronic, we nicknamed him ‘Tron’. Once that footage existed, it couldn’t be stopped.”

Neither could Lisberger. After 36 outlines and 18 rewrites, Lisberger finished the screenplay that would baffle Boxleitner. It was The Wizard of Oz in cyberspace. After hacking the corporation that stole his videogame ideas, a hotshot programmer finds himself sucked into a gladiatorial virtual-reality inside the corporation’s evil Master Control Program (MCP).

“Our script was entirely storyboarded,” says Lisberger. “We’d figured out we wanted to film it in live action and combine it with computer animation.” He spent $300,000 developing Tron and secured $4 million budget before realising he need Hollywood help.

No one in Hollywood had any idea what he was jabbering about.”He had these fantastic drawings to get us excited about it,” says Disney chairman Dick Cook. “Most of the people were just kind of looking at each other. ‘He’s trying to tell us this story, inside this computer, and this game, and this guy’s going to be sucked in… Uh huh… uh huh… We didn’t have a clue.”

But that was the clincher: Disney didn’t have a clue about much. Once upon a time, they’d led the special-effects charge with amazing big-screen fantasies like 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea. Now they had Herbie

. Young people weren’t interested in a sentient beetle, they were pouring their dollars into Arcade machines instead as the videogame craze swept America. The Mouse House needed something. Whatever it was, Tron looked like something.

Giving $10 million to a first-director to splash on techniques that had never been attempted made Disney understandably anxious. Lisberger shot a dazzling test-reel in which Frisbee champion Sam Schatz blasted robots from Disney’s 1979 sci-fi flop The Black Hole. The technology worked. The symbolism was clear. Tron was a go.

Many Disney animators refused to work on the movie, fearing that computers would put them out of a job. They were right – but it would be another 22 years before Disney closed its hand-drawn studio in favour of CGI animation. But Lisberger had his dream team. Blade Runner‘s legendary futurist Syd Mead created Tron’s vehicles, including the light cycles, tank and the epic ‘Solar Sailor’. After designing sets and costumes, French comic-book genius Jean Giraud, aka Moebius, re-storyboarded the entire film.

“The combination of those two was just beautiful,” says Lisberger. “Syd is so futuristic and stylish in such a severe way and Moebius’ work is so spiritual and charming.” They would create a fully CG world – every background, every vehicle – populated by live-action human characters. But casting those human characters wasn’t any easier.

ENTER PLAYER ONE

“People would say ‘Am I gonna go out to Disney and play a Pong character in a videogame?'” remembers Lisberger. “I thank God that we got Jeff Bridges.” Coming off the back of The Last Picture Show, Thunderbolt And Lightfoot

and Winter Kills

, Bridges was a rarity: a bankable Hollywood star who loved working with first-time directors. “It was kind of risky, but it’s a tough one to turn down because it’s a chance to do something very new,” remembers Bridges. “I got to play a character who’s sucked inside a computer! Oh my god!”

Boxleitner signed up as soon as he heard Bridges was on board (“My god. Really? I’ll do it!”). Lured by talk of a huge special-effects thriller with motorcycle chases and tank battles, Brit thesp Peter O’Toole had been lined up to play Sark, head of the evil corporation. He was imagining Star Wars. He turned up to find a black screen and nothing else. “He wanted to know where the tanks where!” laughs producer Donald Kushner. Goodbye O’Toole, hello David Warner.

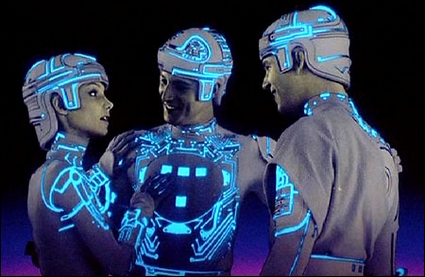

Hard to imagine O’Toole wearing skin-tight white pyjamas and a crash helmet. Tron’s wardrobe looked ridiculous. Boxleitner couldn’t believe it: “I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding. Where are the pants? Where. Are. The. Pants?'” Caddyshack actress Cindy Morgan immediately disappeared from the set. They found her in the gym, where she refused to leave until she’d lose 5lbs. Bridges had his own problems, largely with the ‘dancebelt’ concealing his gentleman’s bulge. “It’s like a G-string,” he says. “No, there wasn’t much sitting down on the set of Tron…”

Every day during shooting, Lisberger brought in the latest videogames and encouraged everyone to play them. “If you were on a streak, people would gather around and he would postpone shooting,” says Bridges. “Then you’d pop right into the scene with this adrenaline buzz.” It was the only way Lisberger could give them an idea of what they were doing on that empty black stage. “Steven would say, ‘You’re on the Solar Sailor,'” says Morgan. “You’d be like, ‘Okay, the ‘Solar Sailor’…’ Then he’d show me the picture. I said to him, ‘Steven, I don’t really understand a lot of what I’m saying.’ He said, ‘No problem. Just say it with conviction.’

PIXEL POWER

Ironically, there was little computer wizardry to the live-action footage. But a lot of processing power. After shooting the actors in white costumes against a black background, the live-action footage was projected on to separate layers of film. “There were about five elements to each frame,” explains Lewell. “The face element. The body colour element. The circuitry glow element. Facebodycircuit composite. The CG background.”

But first, every single frame of the 75-minute movie was blown up to a 14-inch print and colourised using gel-paint for the glowing elements. “We treated live-action footage like individual animated cells,” says conceptual designer Richard Taylor. It created extraordinary neon effects. And it would never be done again. Truckloads of sheet-film and more than 500 people (including 200 hand-painters in Taiwan) were needed for the agonising post-production.

But Tron’s most innovative and difficult sequences involved using 3D CGI for to create the matrix-like computer world and its tanks, spacecrafts and bikes. Most thrilling of all was the breakneck ‘light cycle’ duel around a deadly green grid. A young Disney animator was working on Mickey’s Christmas Carol at the time and never forgot the footage he glimpsed. “The light cycle sequence was the first scene I can remember them working on,” remembers John Lasseter. “This was some of the very first computer animation I’d ever seen. And it absolutely blew me away.”

Lasseter, though, had no idea how hard it had been to create. Main problem? The technology simply didn’t exist. “We had no tools to make things move, let along move with personality and drama,” says animator Bill Kroyer. “What was terrifying about Tron, was we would plot out vehicles chasing each other, going down canyons, with cameras flying through the air, twisting and rolling and diving… And we could only see one frame at a time!” Kroyer had just one option. Break every sequence down, frame by painstaking frame. “Let’s say you’ve got an object, like a light cycle,” he says. “For every frame that it moves, you need at least six numbers to describe its position. So that means for 100 frames, you need 600 numbers of data. 100 frames is four seconds. To describe whether one thing is. You can imagine us sitting their writing numbers on graph paper, right?”

Which is exactly what they did. “We gave these computer guys six rows of handwritten numbers for every frame. And they hand-programmed them in! They typed them in!” This was 1981. There were no USB drives. Or floppy disks. Tron contains just 15-20 minutes of CG, but it was a staggering amount – nobody had ever attempted it before. The one-of-a-kind computer used to create Sark’s carrier was as big as four deep-freezers put together.

NEXT GENERATION

Disney thought they had a sensation on their hands. They predicted at least $400 million at the US box-office. In the end, Tron’s arcade videogame out-grossed the movie itself. Losing a blockbuster head-to-head with Steven Spielberg’s ET in the summer of 1982, Tron grossed just $33 million.

“It was difficult for Disney to say we’ve got the cutting- edge movie and we don’t have the cute, cuddly movie,” says Lisberger. “And I’m sure they were envious of the money happening on the other side of town. We were just so proud of the fact that it worked, because it was such a highly experimental film.”

Everyone agreed on one thing: Tron’s CG special effects were utterly groundbreaking. So groundbreaking, in fact, the Academy Awards refused to nominate them. “They said we cheated!” says Lisberger. “Which in the light of what’s happened is just mind-boggling.” Seven years later, James Cameron’s The Abyss won the Best Visual Effects Oscar for using the same technology..

Today, even an obsolete PlayStation2 game is infinitely more complex than Tron. But Lisberger’s team stood at the edge of where technology was and dived off, taking cinema with them into the future. “For me, it will always stand as one of the milestones of computer animation,” says Lassseter. “Without Tron, there would be no Toy Story.”

Then came the big surprise at last year’s Comic Con: test footage from “the next chapter” to Tron. “The audiences have grown immeasurably since its initial release,” said Disney chairman Dick Cook. “I think the world is ready for a new Tron.”

Inked by Lost writers Edward Kitsis and Adam Horowitz, TR2N sees Bridges and Boxleitner reprise their roles, with Troy’s Garrett Hedlund starring as a man pulled into the computer world like Bridges’ character three decades ago.

“But it’s only a game,” whimpers the light cyclist in TR2N’s show-reel. Bridges stares at the screen: “Not anymore…”

Publication: Total Film